Several

months ago, I reviewed Barbara Kingsolver’s New York Times Bestseller Flight

Behavior. The story, whose premise is climate change and its affect on the monarch

butterfly migration, is told through the eyes of Dellarobia Turnbow, a rural

housewife in Tennessee, who yearns for meaning in her life. In the opening,

Dellarobia stumbles upon a monarch massing in the forested hills above her farm.

Although Dellarobia doesn’t realize it yet, that

moment proves life-changing for her:

“A small shift between cloud and sun altered the daylight, and the whole landscape intensified, brightening before her eyes. The forest blazed with its own internal flame…The mountain seemed to explode with light. Brightness of a new intensity moved up the valley in a rippling wave. Like the disturbed surface of a lake. Every bough glowed with an orange blaze…Trees turned to fire…The flame now appeared to lift from individual treetops in shows of orange sparks, exploding the way a pine log does in a campfire when it’s poked. The sparks spiraled upwards in swirls like funnel clouds….It was a lake of fire, something far more fierce and wondrous than either of those elements alone. The impossible…She was on her own here, staring at glowing trees…Unearthly beauty had appeared to her, a vision of glory to stop her in the road. For her alone these orange boughs lifted, these long shadows became brightness rising. It looked like the inside of joy, if a person could see that. A valley of lights, and ethereal wind. It had to mean something.”

Since

that review, COSEWIC (the committee on the status of endangered wildlife in

Canada) reported that the monarch is now officially “endangered”, victim to

habitat loss of wintering grounds (through illegal logging) in Mexico, along

with increasing destruction of milkweed caterpillar breeding habitat by drought

and insecticide in Canada and the United States. While GMO corn, canola and

soybeans have been engineered to be immune to the herbicide Round-Up

(glyphosate), which is used liberally in large corporate farms, milkweed and

other native “weeds” are destroyed.

The

monarch butterfly migration is now recognized as a “threatened process” by the

International

Union for Conservation of Nature. The monarch has precipitously

declined—by 90% in the last two decades since Round-Up was aggressively

introduced. Our role in Canada is paramount as part of the monarch’s cycle.

Overwintering butterflies leave Mexico in early spring and migrate into the

southern US, where they lay their eggs on milkweed plants before dying. Like in

a relay race, the caterpillar offspring feed exclusively on milkweed, then as

adults migrate further north into Canada to reproduce again and then return to

Mexico to overwinter.

Future generations of monarchs, faced

with changing climates, may have a hard time finding their way home, writes

Nayantara Narayanan in a recent Scientific

American article (2013). “A monarch butterfly navigates

using a sun compass in its mid-brain and circadian clocks in its antennae. But,

until now, what makes a monarch reverse its direction has remained a mystery.

New research shows that the chill at the start of spring triggers this switch. Monarch

butterflies, having flown south in the fall, reorient themselves and start

flying north after they've been exposed to lower temperatures, according to the

study published … in Current Biology.”

Researchers had to “go from signal to behavior” to figure it out. They

determined that with temperature being a critical trigger for the monarch’s

northward journey, climate change could be a “big spoilsport in its mass

migration.” Unruly and unseasonal storms coupled with microclimate degradation

(e.g., logging forests and killing milkweed through drought), are impacting

monarch survival.

The monarch butterfly is just one

species—a sentinel, if you will—in what many scientists are calling the largest

mass-ever extinction in Earth’s history; and one caused by runaway global

warming. Two hundred and fifty million years ago, 90% of all living things were

wiped out in the Permian mass extinction. Researchers in Canada, Italy, Germany

and the US argue that volcanic eruptions pumped massive amounts of carbon

dioxide into the air, causing average temperatures to rise by eight to 11°C in their paper in the journal Palaeoworld. This melted vast amounts of

methane (just like what is currently happening in the shelf sediments and permafrostregions of the northern hemisphere), causing temperatures to soar even further

to levels “lethal to most life on land and in the oceans.”

Climate change—and all that is associated with it—is altering

our planet irreparably, one sure-footed step at a time. And it is doing this regardless of

geographic boundary, political affiliation, scientific knowledge or religious

belief. Climate change is a global phenomenon that can provide us with the very

best opportunity to unite as a global community.

In

2014, Canada, the U.S. and Mexico cooperated as Justin Trudeau, Barack Obama

and Enrique Pena Nieto signed the North American Climate, Clean Energy, and

Environment Partnership Action Plan—something, which I wonder if the current U.S.

administration will now honour.

Focusing

on the monarch or any other sentinel is a sound rallying approach that can have

significant cumulative effects. The entire world is inexorably linked, after

all.

You

save the monarch; you save the world.

Kingsolver ends her book with Dellarobia caught in a mountain

flood that may take her life; yet, she remains suspended—transfixed in the

moment of the miracle unfolding before her. The monarchs survived the winter

and are taking flight:

“The vivid blur of their reflections glowed on the rumpled surface of the water, not clearly defined as individual butterflies but as masses of pooled, streaky color, like the sheen of floating oil, only brighter, like a lava flow…Her eyes held steady on the fire bursts of wings reflected across the water, a merging of flame and flood. Above the lake of the world, flanked by white mountains, they flew out to a new earth.”

Let us hope that we are part of that new earth.

Things that you can do to

help:

- Plant a butterfly garden. Add plants that take the monarch from tiny egg to caterpillar to chrysalis to adult. These include plants in the milkweed family and nectar-rich blooming plants. Most nurseries sell pollinator mix seeds.

- Plant milkweeds in your garden. Monarchs lay their eggs on milkweed plants. The adults get most of their energy from the nectar of plants.

- Place your garden where it receives lots of sunlight but is also protected from the elements. You can create a shelter using trees, shrubs and perennials as well as logs and stones. Flat stones can serve as hot spots for butterflies to get warm.

- Write your MLA / MNA / MPP and the minister responsible for environmental issues. Let them know you are concerned. Letters are important and taken very seriously by government; they understand that for every letter sent there are many who think similarly but aren’t writing.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s recent book is the bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” (Mincione Edizioni, Rome). Her latest “Water Is…” is currently an Amazon Bestseller and NY Times ‘year in reading’ choice of Margaret Atwood.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s recent book is the bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” (Mincione Edizioni, Rome). Her latest “Water Is…” is currently an Amazon Bestseller and NY Times ‘year in reading’ choice of Margaret Atwood.

Every year, near Christmas,

Every year, near Christmas,  Margaret Atwood is a winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the Prince of Asturias Award for Literature as well as the Booker Prize (several times) and the Governor General’s Award. Animals and the environment feature in many of her books, particularly her speculative fiction, which reflects a strong view on environmental issues.

Margaret Atwood is a winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the Prince of Asturias Award for Literature as well as the Booker Prize (several times) and the Governor General’s Award. Animals and the environment feature in many of her books, particularly her speculative fiction, which reflects a strong view on environmental issues.

“

“ “The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries From a Secret World” (Greystone Books) by Peter Wohlleben. In The Hidden Life of Trees, Peter Wohlleben shares his deep love of woods and forests and explains the amazing processes of life, death, and regeneration he has observed in the woodland and the amazing scientific processes behind the wonders of which we are blissfully unaware. Much like human families, tree parents live together with their children, communicate with them, and support them as they grow, sharing nutrients with those who are sick or struggling and creating an ecosystem that mitigates the impact of extremes of heat and cold for the whole group. As a result of such interactions, trees in a family or community are protected and can live to be very old. In contrast, solitary trees, like street kids, have a tough time of it and in most cases die much earlier than those in a group. Drawing on groundbreaking new discoveries, Wohlleben presents the science behind the secret and previously unknown life of trees and their communication abilities; he describes how these discoveries have informed his own practices in the forest around him. As he says, a happy forest is a healthy forest, and he believes that eco-friendly practices not only are economically sustainable but also benefit the health of our planet and the mental and physical health of all who live on Earth.

“The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries From a Secret World” (Greystone Books) by Peter Wohlleben. In The Hidden Life of Trees, Peter Wohlleben shares his deep love of woods and forests and explains the amazing processes of life, death, and regeneration he has observed in the woodland and the amazing scientific processes behind the wonders of which we are blissfully unaware. Much like human families, tree parents live together with their children, communicate with them, and support them as they grow, sharing nutrients with those who are sick or struggling and creating an ecosystem that mitigates the impact of extremes of heat and cold for the whole group. As a result of such interactions, trees in a family or community are protected and can live to be very old. In contrast, solitary trees, like street kids, have a tough time of it and in most cases die much earlier than those in a group. Drawing on groundbreaking new discoveries, Wohlleben presents the science behind the secret and previously unknown life of trees and their communication abilities; he describes how these discoveries have informed his own practices in the forest around him. As he says, a happy forest is a healthy forest, and he believes that eco-friendly practices not only are economically sustainable but also benefit the health of our planet and the mental and physical health of all who live on Earth. “Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants” (Ecco) by Richard Mabey. “They’re better for you than you think,” says Atwood. “They hold the waste spaces of the world in place, and you can eat some of them.” Ever since the first human settlements 10,000 years ago, weeds have dogged our footsteps. They are there as the punishment of ‘thorns and thistles’ in Genesis and , two millennia later, as a symbol of Flanders Field. They are civilisations’ familiars, invading farmland and building-sites, war-zones and flower-beds across the globe. Yet living so intimately with us, they have been a blessing too. Weeds were the first crops, the first medicines. Burdock was the inspiration for Velcro. Cow parsley has become the fashionable adornment of Spring weddings. Weaving together the insights of botanists, gardeners, artists and poets with his own life-long fascination, Richard Mabey examines how we have tried to define them, explain their persistence, and draw moral lessons from them. One persons weed is another’s wild beauty.

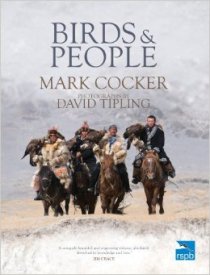

“Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants” (Ecco) by Richard Mabey. “They’re better for you than you think,” says Atwood. “They hold the waste spaces of the world in place, and you can eat some of them.” Ever since the first human settlements 10,000 years ago, weeds have dogged our footsteps. They are there as the punishment of ‘thorns and thistles’ in Genesis and , two millennia later, as a symbol of Flanders Field. They are civilisations’ familiars, invading farmland and building-sites, war-zones and flower-beds across the globe. Yet living so intimately with us, they have been a blessing too. Weeds were the first crops, the first medicines. Burdock was the inspiration for Velcro. Cow parsley has become the fashionable adornment of Spring weddings. Weaving together the insights of botanists, gardeners, artists and poets with his own life-long fascination, Richard Mabey examines how we have tried to define them, explain their persistence, and draw moral lessons from them. One persons weed is another’s wild beauty. “Birds and People” (Jonathan Cape) by Mark Cocker. “Vast, historical, contemporary, many-levelled,” says Atwood. “We’ve been inseparable from birds for millenniums. They’re crucial to our imaginative life and our human heritage, and part of our economic realities.” Vast in both scope and scale, the book draws upon Mark Cocker’s forty years of observing and thinking about birds. Part natural history and part cultural study, it describes and maps the entire spectrum of our engagements with birds, drawing in themes of history, literature, art, cuisine, language, lore, politics and the environment. In the end, this is a book as much about us as it is about birds.

“Birds and People” (Jonathan Cape) by Mark Cocker. “Vast, historical, contemporary, many-levelled,” says Atwood. “We’ve been inseparable from birds for millenniums. They’re crucial to our imaginative life and our human heritage, and part of our economic realities.” Vast in both scope and scale, the book draws upon Mark Cocker’s forty years of observing and thinking about birds. Part natural history and part cultural study, it describes and maps the entire spectrum of our engagements with birds, drawing in themes of history, literature, art, cuisine, language, lore, politics and the environment. In the end, this is a book as much about us as it is about birds. will fare in a shifting political wind, these books offer diverse insight, a fresh and needed perspective and critical connection with our natural world–and each other through it.

will fare in a shifting political wind, these books offer diverse insight, a fresh and needed perspective and critical connection with our natural world–and each other through it.