The sudden appearance of a wormhole causes the disappearance of

astronaut Jim Marcell during EVA on the space station, followed by associated calamitous

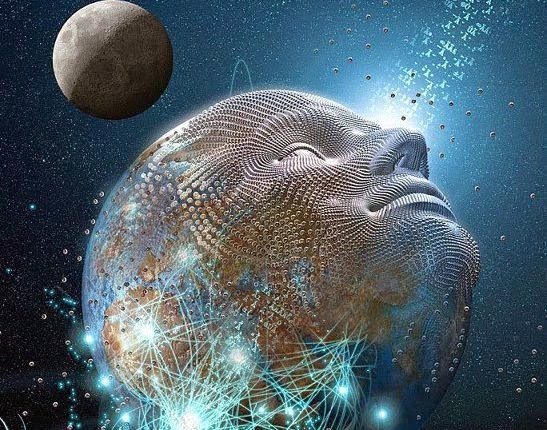

phenomena on Earth. Giant dark spherical clouds then appear and settle all over

the Earth, disrupting the world’s population, and setting in motion a series of

fearful and aggressive reactions by various sectors of humanity; as expected, the

military of each nation mobilize, ready to attack. Some do attack, with no

consequence.

With the help of the military’s groundbreaking transhumanism

technology, the international space agency sends two transhuman (Human 2.0)

astronauts into the wormhole (called the Void) on an information-seeking (and

peace-seeking) mission. The astronauts have been modified by advanced robotics

to withstand the pressures of the “throat” of the wormhole as they embark on

humanity’s first interstellar—possibly inter-dimensional—journey in search of

extra-terrestrial sentient life and its intent. One of the astronauts is a

soldier, armed with additional weapons built into his physiology. The other is

the Space Agency’s chief cosmologist, Jessica Johnson (played by Kosha Engler).

|

| Wormhole viewed from the International Space Station |

When the mission returns unexpectedly, and without the soldier, the space

agency races to discover what happened on the “other side.” Of particular

interest is evidence indicating that the ship had been away much longer than

the days it was actually gone. Johnson later reveals that the soldier had

suddenly disappeared from the cockpit and reappeared outside. She saw him stare

at his arm, which then detonated like a nuclear bomb—no doubt because his arm

was indeed something of that nature.

|

| Jessica as Human 2.0 |

The tag line of the movie says: “to find our place in the

universe, we must venture beyond our boundaries.” This imaginative indie film

by Hasraf Dulull is all about breaking boundaries and transcending beliefs:

such as mission director Gilian’s first lie to her daughter (to contain a

bigger lie by the space agency); and chief cosmologist Jessica conquering ethical

barriers to embark on a journey that will irrevocably change her.

|

| Gilian and Grant watching the take off |

The story unfolds like a docu-drama, making use of interviews

with key people and retrieved footage amidst dramatic narrative (similar to

Blomkamp’s District 9). The mixed

narrative creates an immediacy that grips us emotionally and deeply connects us

to the characters in a real-life way. Characters are portrayed as ordinary

people who find themselves in extra-ordinary circumstances and performed with

genuine candor, particularly the mission commander Gillian Laroux (Jane Perry) who

plays a Canadian.

The Beyond appeals to our senses and sensibilities,

challenging our assumptions and definitions of what it is to be human through

our values, hopes and fears. Told with an unassuming realism, The Beyond

is really a simple, yet deeply meaningful story that asks the big questions—and

leaves it for us to answer them.

|

| One of the dark orbs over Earth |

The climax, discovery and resolution is really more of a question.

I was somehow unprepared for the discovery and emotionally struck by its trajectory

into the denouement. Some reviewers on the Internet were off-put by the shift

following “the discovery” that preceded the denouement at the end. I found

closure for the chief cosmologist, who had sacrificed her life to seek answers

and find a solution for humanity; however, the question remained: what is that

solution for humanity? What does that solution look like and how does it

encompass more than us? The movie doesn’t have a tidy end; its solution is

veiled with more questions.

|

| Catastrophe... |

The film ends with a cautious hope, implicitly asking that big

question: are we (humanity) worth saving? When Jessica asks why humanity was

offered a second chance by benevolent beings way beyond our comprehension, the returned

Jim Marcell (currently a spokesman for the aliens) shows her the GAD (Golden

Archive Drive with video images of Earth and humanity—basically our “hello”

message to extra-solar life like the one placed onboard NASA’s Pioneer missions)

that had accompanied the ship into the wormhole. The message displayed scenes

of mothers and their children, people laughing in joy; it also showed scenes of

other aspects of this beautiful planet worth saving: the ocean surf, the

forests and wildlife. In our hubris, we have lost our perspective about this

planet. Perhaps, it wasn’t so much humanity the alien beings intended to save

but the Earth itself; we just come along with it. The Earth is, after all, a

beautiful, vital and unique world, rich with life-giving water, trees, animals,

creatures of all kinds in a diverse network of flowing and evolving beauty. A

planet worth saving and that, frankly, functions better without us.

So, the question remains: is humanity

worth saving? For centuries we have hubristically and disrespectfully used,

discarded and destroyed just about everything on this beautiful planet.

According to the World Wildlife Federation, 10,000 species go extinct every

year. That’s mostly on us. They are the casualty of our selfish actions. We’ve

become estranged from our environment, lacking connection and compassion. That

has translated into a lack of consideration—even for each other. In response to

mass shootings of children in schools, the U.S. government does nothing to curb

gun-related violence through gun-control measures; instead they suggest arming

teachers. We light up our cigarettes in front of people who don’t smoke and

blow deleterious second-hand smoke in each other’s faces. We litter our streets

and we refuse to pick up after others even if it helps the environment. The

garbage we thoughtlessly discard pollutes our oceans with plastic and junk,

hurting sea creatures in unimaginable ways. We do not live lightly on this

planet. We tread with incredibly heavy feet. We behave like bullies and, as The Beyond points out, our inclination

to self-interest makes us far too prone to suspicion and distrust: when met

with the unknown, we respond with fear and aggression rather than curiosity and

hope. Something we need to work on if we are going to survive.

As I mentioned above, The

Beyond is a simple film made well; something not easy to accomplish. The

film delved into existential questions with an emotional intelligence that was

both sensitive and insightful. As Gillian Laroux says in the end: “I hope we

won’t make the same mistakes of the past and prove that we are in fact worth

saving.” Ultimately, I found The Beyond

a refreshing change from the senseless soul-gutting violence, and sordid

aimless or overly-complicated plots that currently populate most of our current

science fiction TV and movies.

The Beyond marks the

directorial debut of Dulull, a VFX wiz who spent a year shooting and working on

this project (previously titled The Void).

Changing the title from The Void to The Beyond is itself an interesting

shift in what the film represents and suggests.

Let us tread more lightly on this planet, then…And perhaps we too

will be worth saving. Perhaps our destiny won’t be a void but a transcendence

beyond…

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.